If used, I'm hoping it'll push learners' engagement, dignity, comprehension, creativity and standards mastery to the top levels we're looking for. Of course, as always, I'd love your feedback and suggestions.

Thursday, December 5, 2013

Anatomy of Question-Driven Learning

For those of you who were kind enough to read my last post on reading and literacy strategies, you already know that I'm a tremendous advocate for using questions to drive growth, whether it's in a classroom or a professional development workshop (so I'm speaking to all sorts of educators and salespeople out there). In case you missed the last post, which goes a bit into depth about the questions themselves, here a link. In this post, however, I'm hoping to further the conversation about clarifying some best practices around using questions to drive pedagogy.

If used, I'm hoping it'll push learners' engagement, dignity, comprehension, creativity and standards mastery to the top levels we're looking for. Of course, as always, I'd love your feedback and suggestions.

If used, I'm hoping it'll push learners' engagement, dignity, comprehension, creativity and standards mastery to the top levels we're looking for. Of course, as always, I'd love your feedback and suggestions.

Friday, November 22, 2013

Strategies to Help Readers When They Struggle

My kids read well. I know it's awful to brag like that, but they've worked hard at it, and I'm proud of them. They're proud of themselves, which is even better. My daughter (8) is very casual and matter-of-fact about things, so she doesn't talk about much, but my son (6) is obsessive. He loves his teachers, and he loves talking about fun things that he's learned, especially when fun animals and their names are involved. Both kids love technology and love to teach, by the way, so creating this chart based on some of the literacy strategies my son came home with was a great time full of suggestions and giggles from each, with a bit of tech assistance from me.

I am fascinated by elementary literacy work, believing that it's not only a true joy to share reading with young children, but also that there is no better gift we can give to kids than to help them access and truly revel in the pleasure of story telling, information consumption and the critical and creative thinking that go hand in hand with all quality text. If we could truly get to a place where we were universally getting early childhood literacy right - a place, I believe that the CCSS can bring us - kids would be in good shape. Helping them handle a trouble spot on a page, or a troubling page for that matter, is a first step that I hope the chart below can help with.

I spent a lot of my career working in and chairing secondary English departments. I am a tremendous proponent of schools guiding their practices around the inclusion of modern literacies. I cringe when secondary teachers say that teaching reading isn't their job, which I've heard from English teachers as well as other content area teachers. If we can't help students access, consider, make sense of and communicate ideas about information and people, we've lost the fight. So, I was thinking to myself about a secondary version of "Chunky Monkey," "Eagle Eye," and "Loggy Froggy." I'm not officially trained as a literacy instructor, but after some consideration and a bit of research, I came up with these seven components to literacy instruction.

These are all very important and highly useful. I would bet that they could play a role in just about any text you'd like your students to experience, or anything they find on their own. I'm sure you noticed, though, that I gave the most geography to "Asking Questions." This, in my opinion, is the holy grail of instruction. It allows students to engage each other and the text at multiple levels of abstraction. It creates a shared experience with a text. It helps students identify things that they are truly unsure of or curious about. It's the basis of inquiry and engagement. It's the reason why I love the follow-up chart so much.

Looking it over for the first time, a major joy came over me when I realized that I could use this at any time for a host of reasons in a number of ways. I'll give you a few minutes to look at it and consider its potential before you scroll past and see the beginning of my suggestions.

Can you imagine:

Starting in the top left and moving around to the bottom right as a class is introduced to and then begins to grapple with new material?

Students writing their own questions, some from each quadrant, as a review at the end of a unit or as a "do now" after completing a reading for homework?

Including all of your students in a class discussion by allowing less confident students answer more accessible questions until they are showing a willingness to chime in during class?

Formatively tracking which types of questions seem to be a struggle for which students and helping them focus on those problems in specific groups?

==================================================================================================================================

I hope these charts have helped. As always, I openly welcome your input, additions, and - of course - questions.

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

Using Tweet Deck to Keep up With Chats

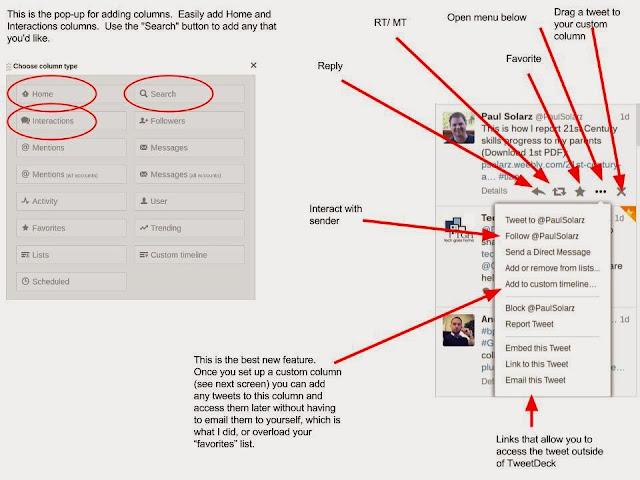

As I've become more invested in Twitter, the basic site became inadequate for a few reasons, mainly having to do with participation in chats. If you haven't gone there yet, chats, I feel, are the best way to meet people, develop connection, find resources and truly leverage Twitter to its full capacity as a professional development tool. The problems faced when using the official site stem from there being only one screen at a time, meaning that I can't view the chat's feed, my home feed and my interaction feed without putting each in a different browser tab and toggling between them. This could work, but it's not ideal, and there are times when I want to take part in 2 or 3 chats at the same time. That's when I found TweetDeck. I feel a bit late to the Twitter world in general, so I wasn't on when this was independent of Twitter. Now, the home page says "TweetDeck by Twitter," so it seems that even Twitter has realized that the original screen lacks a bit.

Please note that I'm a capable beginner. I can do what I do pretty well, and I've learned a few tricks that I'll share here, but this is not a complete guide to TweetDeck. Here's the basic screen. The most important thing to know is that you'll now be working with multiple columns that are generated using the "add column" link on the left and then the "search" tool within that screen. You can, if you'd like use the "search" tool first and then click "add column" once your search shows up.

Once you have columns created, you can set up them and use them as you'd like, using the feature found below. One of the things I'm most excited about is the "content" filter that can be set for each column. While there are other options that I'm sure are powerful, this allowed me to keep spam from clogging up my feed during last week's #satchat. For now there's just a lot of spam, but I'd bet - now that Twitter, like Facebook before it, is now a publicly traded company - that in-stream ads are coming, just like on Facebook since its IPO. This language filter could help as Twitter and TweetDeck already tend to slow to a crawl during busy chat times, so cleaning out the spam (and potentially the ads) has been a big help.

These last two screen shots will show you what the "custom timeline" feature is all about:

Friday, November 15, 2013

Feet Forward...Fingers Crossed

There’s something about the moment when I ask my 6 and 8 year olds: “Who’s in charge of your behavior?” that makes me seem like I’ve been drinking the punch at some sort of professional development activity for social workers. I wait for an answer with an overblown sense of anxiety over whether or not my kids are starting to internalize the amount of absolute agency and accountability that I want them to own in their lives. Depending on the time of day, the amount of sugar they’ve had, the actual severity of the situation and how calmly I can ask them, I may have to redirect and add a prompt, but we’ve managed to get to a point where they consistently say: “I am.”

If all goes well, this will grow within them along an eight-fold path from a piece of knowledge to an understanding they work to act upon and on to something that they fully internalize in their future. I want this for them because I know how important intrinsic control is to success. Those people who believe they have the ability to shape their futures find much higher levels of success than those who think all or most things are out of their control. Also, I philosophically believe it and - on a Dad level - hope that it will one day be one of those things they’ll proudly tell people I taught to them.

We are always in charge of the way we act in the world and the way we react to what happens in the world. And this covers the the first part of my mantra: Feet Forward. I know that I always need to point my actions and beliefs (my feet) in the direction of what I want and move that way.

What I haven’t told my kids yet is that I’ve found life in general to be rather random, quirky and outside of my ability to explain (I’m a lay-existentialist). I keep my proverbial fingers crossed because I don’t think enough of the world happens in a predictably logical way for me to count on it. Life certainly doesn’t always follow suit when I set the stage for things to happen as I’d like them. There just aren’t any guarantees in life. So, I hope some pixie dust falls and brings a bit of order to the chaos. I hope for just a bit of luck to help me out because I know that even if there is a divine force of justice or a sense of karma and fate in the world, that my daily plans, needs and goals aren’t of enough universal consequence to get - or deserve, for that matter - any attention

These two pieces fit together simply and nicely to form advice that I not only live by, but also offer up to my children, friends, faculty and students. Feet forward...fingers crossed. I cannot guarantee or often even make sense of what’s going to happen in the future, but I can work hard to identify those things I control, work to accomplish them and give myself at least the best fighting chance I can to make things roll my way. I’m not going to start picking up a bunch of bad habits just because my mother passed away from cancer after living a healthy life. I’m instead going to realize that I’ll do what I can and life will happen as it does, often regardless of my efforts.

To bring this idea home, I’ll tell you a bit about my current job search and prompt us all to consider conversations we have with colleagues, families and students. My family and I chose to relocate this year in order to bring what’s left of our family as close together as possible after a death in the family. I gave up a great job in NYC schools to do it, but I didn’t count on good vibes to help get a new position. I’ve been working on transferring my certifications for over a year now, doing whatever I can to make connections and network on Twitter and LinkedIn, contacting people and meeting whomever I can in person and applying for a lot of positions. The fact that I haven’t yet found a new position doesn’t mean that I’m not going to work again or that I’m going to give up trying and amp up a Second Life account; it just means that I need to keep mapping a road through the ever-changing landscape. What can I do (Feet Forward) in a situation where what I’ve been trying isn’t working (still keeping my Fingers Crossed)?

As for everyone else out here, think about the increasingly difficult and chaotic world in which so many are now living. Even though the idea works for victims of horrendous disasters, it’s also helpful to realize that our everyday life is a tough place to be at times. Are you an educator trying to figure out how to reach all of those students you see everyday? An administrator stressed about testing data and RTTT compliance? A parent whose child seems to be having a hard time, despite being in a creative classroom and a friendly school? Are you out of work or wondering how to pay for housing or college or healthcare as the costs exponentially exceed inflation and the average workers’ pay increases? Regardless of how tough things are, I’m going to suggest you seek out one thing you can do at time that will best position your situation to improve. Find someone to help. Do a bit more research. Take care of a priority need. Get some sleep for a change. Chances are that there will be at least one thing you can do and that the paralysis you’re currently experiencing may have to do with your trying to fix too many things at once.

For me, I’ve just applied to be a substitute teacher, after fourteen years in the profession, finishing up close to two advanced degrees (one formal and the other credits in MA level certification programs) and becoming certified all the way through superintendency in three states. Substituting is not what I’m going to do forever, but it is once step in the direction to making that reality a reality. I’m also not giving up on the big-picture search, but I need to be looking at both the forest and trees instead of losing one to the benefit of the other.

Your thoughts, suggestions, and alternatives are always welcome.

Sunday, November 10, 2013

A Review of Starr Sackstein's TEACHING MYTHOLOGY EXPOSED

As a career English teacher and literacy advocate who started junior high school and continued through high school not reading, I firmly believe in the adage that says non-readers are actually avid readers who just haven’t yet found the right books. There are a lot of tells regarding when we’ve found a book that’s for us, ranging from not being able to put the book down to the amount of notes we may scribble in the margins and the connection we feel with the author during and after we’ve read the book. Some titles have worked for me because of the time and circumstances in my life, while others have a perspective that either reinforces something I’m proud of or brings me to a new and positive place. Within the volumes of books about contemporary education and teacher practice that I’ve seen, skimmed and read, Starr Sackstein’s Teaching Mythology Exposed stands on its own for both its fully honest and transparent content and it’s particularly unique style.

Part practical field guide and part guiding compass for those philosophical, political, and self-deprecating moments in all professionals’ lives, Sackstein here takes on a role of advocate, mentor, struggling colleague, humble practitioner, brazen realist, and tireless optimist that can only come from years in a classroom, a generous spirit, and a sense of honesty that constantly reminds the rookies and veteran teachers who are smart enough to engage with her that: “We mustn’t get discouraged with our mistakes, but rather use them to push harder and become better.” And who else would we like that message to come from, than a National Board Certified Teacher with a dozen-plus years in the classroom, deep chops hewn by both suburban and New York City public schools, and a career-changer’s objectivity that helps her thread much-needed lines through the gap between the truths perceived by many as they enter and acclimate into teaching and the reality they find in schools.

Sackstein’s book is too professional to be called a mere self-help book, but it’s structure is too interactive, and her tone is too personal for it not to be a contender for any teacher’s proverbial back-pocket, something to be kept close by through any situation. It is essentially guided by “myths” about teaching and being a teacher, what she defines as “...the assumptions about our chosen path [that] can often derail the most motivated and productive educators.” Her invitation to “...transcend these misconceptions of face being buried by them” should be attractive to all of us, hopefully before a new teacher becomes part of the statistics about leaving the profession early or a veteran becomes pointlessly and/or fruitlessly embattled in a political standoff or pedagogical quagmire. This book is the truth that the best intentions, technology, lesson plans or program of studies offerings can fail in a public school if we are smart about our approach to implementation and preservation. It’s a complex, social profession, after all. Context and relationships will always drive our success.

Because Sackstein’s a teacher and not a soothsayer or a politician, she avoids prescriptions and, instead, approaches this material with anecdotes, humble reflections, questions, and examples. Myths including “Teachers can prepare for everything, all the time,” “Social media doesn’t belong in school” and “It’s possible to reach every kid, all the time” are fleshed out in their own chapters with sections that define the myth, give an illustrative story from her own career, offer and explain solutions and finally - the most effective piece, I believe - offer up reflection questions so that teachers, teacher teams and classes of any sort could use each section as a discussion guide. It’s also clear that while the book could be read start to finish, it would be just as meaningful if people engaged with whatever myth was most applicable to their work at the time. And this, truthfully, is where the power of her book shows up. I’m sure there were cathartic motivations for her writing, but the book truly comes across as the manifestation of her belief that “...every teacher needs a friend, a colleague and an administrator on his/her side.” Since not all schools have a supportive environment open to discourse and reflection, Sackstein is offering herself as both a potential catalyst to that collaboration and an outlet for reflection in those times when too many educators feel too professionally uncertain or isolated.

It isn’t surprising to me to have found this all in Starr’s book. She and I have, after all, met on Twitter, where she has been an honest and inspiring part of my PLN for almost a year and a half now. In Twitter world, that means that she and I have been in countless conversations and resource-sharing chats, challenging and learning from one another. Being who she is, she also has gone on to push herself and others by leading #jerdchat, #sunchat, and guest moderating other national discussions such as #tlap. For her, education is obviously a calling that requires more than the assumed depth of content knowledge. Success as a teacher hinges on “...knowing that the top of the mountain is always just out of reach” and that as tiring as it gets, “Master teachers look at failure as a growth opportunity.”

I know that “Education is arguably the most challenging and rewarding career in which to become enveloped.” I’m obsessive about my work and have been chewed up by it on mutliple occasions. I’ve happily - and successfully, I’d say - made it through fourteen years as an educator in a variety of districts and a number of roles, but I would’ve approached much of my formative time with just that much more sensibility, compassion, and idealism if I had had Ms. Sackstein’s book with me for the ride. Find her book, Teaching Mythology Exposed, here and all of her other writings here.

Saturday, November 2, 2013

Updating Goal Writing in Standards-Based World

There was a time in the not-at-all-too-distant-past when the only way students (or teachers for that matter) could define a learning outcome was by telling when the last day of school was.

My teachers covered/went over whatever material was next (There were a few who probably did, but I’m doubting many of them had lesson plans or curriculum maps), but there was no effort to contextualize, personalize, reflect, collaborate, process, or engage with multi-media in any way. The Commodore 64s down the hall didn’t even have their own floppy drives (the real ones) yet, and our floors’ wax still held the desks in their rows through most of the year. The only goal I had was get out of high school. I graduated with good grades, but 85% of it was meaningless to me. Except for a few instances, my school experience from grades 7-12 was all about going through motions.

By the time my first “career” (musician) crumbled, and I went back to graduate school in the 90s, things had changed a bit in schools, including the addition of reflection and goal writing for students. The expectations from my teacher ed professors - and then from some of my early administrators - was that my students were writing goals in their notebooks. They would also come to student-led conferences and talk to their parents about these goals. They would tell me about themselves as a reader, writer, thinker, overall student and person. We had “goal sheets” and “personal inventories” of all sorts, each one of which had its own column in our grade books. We also had the curriculum and our lesson plans.

The issue was, though, that throughout my student teaching, graduate courses and time with mentor teachers, I never saw any examples of - or organically knew how to do this myself - teachers using these goals and inventories for anything. We forgot about them. Our (mine for sure) students forgot about them. I even went into an evaluation meeting with a principal; neither of us had any idea what my goals were. Ouch. Was there learning going on? Sure, but not nearly at the level we now expect and know can happen or with the urgency we now know it needs to happen.

Yes, we’re better at writing goals these days (SMART or otherwise), but I’m left unsatisfied, so I’m going to suggest an upgrade here, especially since we are all quickly moving into the standards-based education world that a good amount of states, districts, schools and/or individual teachers have been brave/insightful/innovative/concerned/reflective enough to already put into place. Let me lay out a few “knowns” that are going to bring us forward.

- Students learn better when they’re REFLECTIVE. We must have students thinking about where they’ve been, what they’re currently doing, and where they’re going. They also need to do more than just name these pieces. We know that thinking skills in the upper levels of DOK scales and Bloom’s charts are what the places where learning happens, so let’s prompt them to do things like evaluate their work and create a way to track their progress. Knowing that social learning also helps, can they work these tasks for their classmates’ progress as well?

- Students learn better when they’re AWARE of the outcome(s) they’re working towards. This is the standards-based learning piece. As an administrator, I like nothing less than talking to students who tell me they did “chapter 3” in class or when they either can’t remember what they learned last or don’t know what’s coming next. In a standards-based world, the learning outcomes, the context, and the trajectory of the learning will be clear. Modern educators must be aware that any of these scenarios aren’t the way to promote the highest level of learning possible. Learning should purposefully spiral throughout a course, building on the context from yesterday, towards a transparent end. Mysteries, tricks, and guesses are for game shows. Our work is urgent.

- Students learn better when they’re given AGENCY over aspects of their learning. We all know that we can’t force the horse to drink, but we rarely help the proverbial man figure out how to fish for himself in our classes. I used to love asking my students to tell me if their work was good before they handed it in. Before too long, they knew that if they said “I don’t know,” that I would ask them if they’ve read it / looked it over and send them back home to do so (no late points). Our students have to be positioned in a way that has them thinking about the desired end to their learning, understanding what makes that end desirable and assessing it against wherever they currently are. On top of it, they need to make choices and work to clearly explain how they see themselves bridging the gap between the two.

Ultimately, then, I’m suggesting that we scrap “goal setting.” It’s just not - in my opinion - a clear enough ask for what we actually want and our students actually need. What’ll come in to take their place…”What’s next statements.” Why is this an important upgrade?

In order to understand What’s next, a student would have to :

- Be able to explain what (s)he is supposed to learning in the big and small picture. What’s the full unit about? What’s the connection between today’s lesson(s) and that big picture?

- Be able to express an awareness of where his/her skills and knowledge are with regards to the standards. What is he doing well on? Where is she struggling? What questions does he have? What pieces can she help teach to classmates?

- Be able to plan out a course of learning (with and without assistance and scaffolding) and means of expressing his/her eventually proficiency or mastery with the standards.

Friday, October 11, 2013

Cultivating our K12 Mindset

In Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, he lays out the idea that “greatness” and success are primarily the result of context. People aren’t great by themselves so much as the products of perfect conditions coming together in the right way for the right amount of time. He presents a number of anecdotal success cases from sports and business that exemplify his thesis, explaining that while these people obviously have done great things, top-tier Canadian hockey stars and business execs like Bill Gates have all benefitted from their context more so than their genetics. In fact, he goes on to say that things like IQ and physical stature reach a plateau, beyond which they lose their sense of influence to the person’s life experiences.

I had the most parking-lot moments with Gladwell - I listened to an exceptionally enjoyable version of him reading the book via my audible account while I was commuting to work - while he discussed how this idea manifests when people become aware of it, buy into, and ultimately - in our modern way - try to manipulate it to our advantage. What he was talking about was the modern breed of parents who are trying to raise children to reach the pinnacle of a self-actualized, socially adored, culturally groundbreaking life through what sociologist Annette Lareau termed “Concerted Cultivation.” It’s the idea that child raising shouldn’t be left up to chance; if we know what works and what goals we have in mind, let’s put it all together and create the sort of environment and set of experiences that will foster such greatness in our children.

What this looks like are the lives of children whom we now read so much about these days, those who have pottery classes, sports, music lessons, museum tours, and historical site visits packed between access bottomless technology, stacks of books everywhere they turn, afternoons spent cooking elaborate recipes with their family, international vacations, professionally connected mentors and the philosophical and functional awareness of why it’s important to buy local and organic foods. These aren’t at all bad things to have, of course, but if this were an old-school textbook, I’d have to have a special boxes on the side of each page with colors an alternate font. 1) This can be taken to extremes with such items as Baby Einstein, activities like toddler beauty pageants, birthday parties on the fields of major-league stadiums and the gentrified and safe trophies-for-all world of helicopter parenting. We should note that these extremes all have their damaging sides that range from mind-numbing screen time and a warped sense of beauty and self-importance to a generation of children who haven’t had the benefits of working through and reflecting on struggling and losing. 2)This is the foundation for the achievement gap. It shouldn’t be a shock to know that not all parents have the know-how, the means, the time, the money, the connections, or the backgrounds to put these pieces in place for their children. It’s why there’s a connection between parents’ careers and children’s vocabulary, between life experiences and reading comprehension, and between family income level and students’ success rate.

It’s why families who have yet to experience success in American schools are less likely to have children who find that success.

It’s why American schools need to be sure to step up and be amazingly purposeful on behalf of our students. “They’ll do fine” isn’t good enough, and succumbing to statistics and low expectations is unacceptable. There are just too many students who are “school dependent,” needing us to fill in the spots where their experiences and families’ capacities create a deficit of one sort or another. It does, after all, take a village to best raise a child. Let me, then, speak to a few fixes in our work that need to happen k12, structures and belief systems that I’ve seen become damaging to kids by the time they hit 9-12 and are in our purview to move beyond.

1) Start with a “Growth Mindset.” If you aren’t aware of this idea, Carol Dweck is its champion. Simply put, it means that all children - and people - have the capacity to grow beyond where they currently are. It says that everyone has the capacity to produce high quality work and struggle with big ideas, even if some students need more support, time, or scaffolding to get there. For my own kids, it means that we talk about “still trying” or “haven’t yet been able to” instead “I can’t” or “I’m no good at.” There’s nothing new in saying that people do best when they’re motivated over time to work at something with the necessary supports in place, but we still - for many reasons, I assume but won’t get into here - believe that some can and some can’t and that some deserve and some don’t. There has to be a culture in our schools that helps students and families know how happy we are to have them there and how important it is for us all to work together at becoming better. One of my favorite Twitter chats is hosted by Michele Corbat and other great educators on Monday nights at 9est. It’s called #COLchat and focuses on creating a “culture of learning.” Click here for my Diigo library page for resources on Dweck and growth mindset.

2) Turn the idea of “failure” into the reality of “struggling.” We should only be doing work in school that’s worth doing, and if it’s worth doing, it’s probably not easy and probably can’t be finished quickly. If we force students to work under time constraints, we’re really only assessing what they can do within that amount of time, not what they can do. If we couple that by saying that we’re going to grade you and move on at that point in time, we’re saying that we’re okay with our students having only done 65% of this or having done all of it with 65% accuracy. If it’s important, that shouldn’t be acceptable. If we, instead, pushed students to finish all work, to always improve and reflect upon their initial attempts and to not expect things to happen quickly and easily, they’ll be better off for it. This is what researcher Angela Duckworth calls “grit.” It’s the willing to buckle down, accept a mandate, and work hard to successfully finish a task. Click here for my Diigo library page for resources on Duckworth and grit. Jessica Lahey has written a lot about parenting and children’s failure as well. Finally, you can read my blog post on it.

3) Students’ learning is about them, not about us. If you haven’t yet read Daniel Pink’s book Drive or at least seen the RSA video and/or the TED talk about it, do so. His research pushes us to lose our extrinsic motivators and help students realize that the learning they’re doing in school will make their lives better. Extrinsic rewards such as praise, money, prizes, etc. diminish the value of and respect for any task that’s beyond generic and menial. They need to driven by their own interests and sense of purpose. This is a big one, so I’ll break up the amount of places we detrimentally steal the scene from the stars of our show, the students:

- Grades - I will get into it a bit in my final point (4), but anytime we have students working for a score or a grade, we are most like doing short-term damage to the quality of work and long-term damage to the level of investment a student has in school work. This, by the way, fully includes standardized test scores. Make a goal around improving vocabulary, skill around variety of sentence structures and poetry analysis, not raising test scores. Alphie Kohn has been spot on about this psychology for decades now.

- Avoid approving or giving praise to work until after the student(s) has self-assessed and spoken to next steps. It’s better to agree with students who like their work or further support those who don’t than it is to become the arbiter of good and bad, right and wrong.

- Allow for as much student agency as possible when it comes to class. What processes, products, structures, etc. can you be flexible with? In today’s world of technology and well-researched place for artistic/creative expression, it’s more possible than ever for students to put a personalized spin on the learning they need from our classes. Try using a project-based, essential-question driven approach to curriculum design. If you’re going to draw lines in the sand, be sure they’re important and be clear with the students regarding why they have to do something a certain way. Remember Mark Twain here: “Sacred cows make the best hamburgers.” ELA gurus Nancie Atwell and Kelly Gallagher have written extensively about the power of choice in curriculum.

4) Personally, I think the engine behind all of this is the move to standards based learning and grading. You may have also heard it called competency based learning, mastery learning or achievement grading, but it’s all the same. If educators can identify what we want students know and be able to do (cliche by now), we can help them understand how these standards have become pivotal to a desirable future (read: Career and College Ready) and work with them to unpack experiences that will help them “know,” “comprehend,” “apply,” and “create” as a path to show mastery. I don’t want this to sound easy to implement, but it’s a pretty quick and logical jump away from the traditional system in which teachers use relatively esoteric codes (grades) as a form of feedback that isn’t comparable across teachers or helpful for the students’ actual growth. It’s champions include Rick Wormeli and Ken O’Conner. I’ll also add in that I’ve been a part of an amazingly informative Twitter chat that’s full of resources about Standards Based Grading. Every Wednesday night, at 9est, Darin Jolly and a host of other really reflective and insightful educators get on to #sbgchat.

The bottom line is that we need to - in the best, most positive way possible - jump on board with accepting the mission to concertedly cultivate our students’ experience for their best interests. Knowing that this sort of affective education - the one that brings hearts, minds and actions on board - takes a long time, we have to start with our K or pre-K students and work relentlessly with our students through high-school graduation if we are to succeed. It’s about the right messaging in little moments equally as much as wholesale systemic changes. So, get connected and work with as many educators as you can. Our schools can be better. Our students need them to be.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Try Bringing These Qualities to a Teacher Interview

Hiring teachers is the absolutely most important thing I can do for my students and school as an administrator. My top hopes:

- Kind disposition: Teachers need to embody the truth that students, their families, and their futures are our work. Our job is much more than building relationships with students, but very few students learn at their best from a teacher with whom they have no relationship. Being kind is where those relationships begin.

- Content knowledge: Teachers need to be well versed in their content area’s body of knowledge and skills. Historically, 6-12 ELA has used book lists as a form of curriculum, writing in course catalogues that students will be learning titles such as Great Expectations and The Things They Carried among other titles during a year. This approach is fading, though, because the Common Core makes it clearer than ever that the foundation of our work is based on literacy skills more so than knowledge of specific literature. Of course there are some books and authors that many teachers have found students really enjoy and are excellent fodder for teaching certain skills (think: The Outsiders or Romeo and Juliet), but if it’s the literacy skills on which we’re focusing, students need to read a lot of books and texts that they’re going to be invested in and investigate deeply. Our idea of “content knowledge,” then, has to include not only a breadth of literary knowledge that both fills the cultural canon and touches and inspires the hearts and minds of modern students, but also the pedagogical toolkit needed to masterfully craft the literacy lessons. After all, I’m hiring a teacher to connect with students, not a poet, a critic or an editor of literary anthologies.

- Top notch collaborators: Educating students is very difficult, uncertain work, and the best way to surmount its trials, which we all experience at some point, is to work together towards solutions. My preferred teachers will collaborate with colleagues and administrators about everything they do, asking for advice and sharing resources as much as possible. They also must be interested in accepting families as school partners, which these days means opening up multiple lines of communication, including websites, blogs, Twitter feeds, Facebook pages, and message boards on our SIS as well as connecting with phone calls, emails, face-to-face meetings and volunteer opportunities. Students with families behind them have the best chance of success, so we must work with them. Finally, modern teachers ought to be collaborating with students. An increased amount of choice around content, process and product can bolster engagement, foster perseverance and increase students’ capacity with critical thinking skills. Creating a class in which the teacher collaborates with the students and then allows them to productively collaborate with other students means that this teacher’s students will more likely be active participants in the course instead of passive recipients of material.

- Humble, reflective practitioners: Nobody is absolutely perfect all of the time, and any perfection we enjoy tends to slip away quickly if we try to rest on it. Educators all want their students to continually get better, and I want the same from the faculty. In today’s world, where everything is so new all of the time, nothing is as fruitless as working with professionals who want to complain that their “tried and true” methods aren’t working anymore. I actually like to ask interviewees about the last thing they’ve learned about teaching, what it is that prompted them to learn it, and what they intend to learn next.

Setting a High Bar for Learning

Setting high expectations and standards means, first, that the department’s curriculum must account for students needing to be prepared to successfully create, innovate, decipher, empathize, connect, compete and persevere within an ever growing international cohort of ideas, ideologies, perspectives and cultures. We must secondly acknowledge that all of a school’s and district’s students must be included in that success. The times are too demanding and the stakes too high for anyone to opt out. Finally, we must plan for how to use meaningful assessment data to identify students’ skills, run courses in a way that places them each in opportunities to meet those expectations and establishes means of supporting anyone who needs an alternative and / or additional strategy.

Educators with high standards will have to meticulously craft necessary scaffolds, which I see best being done by having teacher write the curriculum in teams. First, ideas will have the best chance of getting from being proposals to a written curriculum and then to a taught curriculum. When the teachers do the planning and creating, they are more fully invested in the framework and less likely to allow students to give up on themselves in times of struggle. These teams will also serve as the best source of support and feedback loops. If a class or student is struggling or if a teacher is going to try something new and innovative, it’s often important that they have another set of eyes to help them troubleshoot, prepare and reflect. Teachers will often rather do this with their peers and then “show off” when administrators come in to observe than get initial feedback from administration. Finally, creating curricula in teams means that the work will be more cohesive both vertically and horizontally. Setting up such a system for an ELA curriculum, for example, means that writing standards can both play out in numerous content area classes across a grade level as well as progress from year to year. Seeing how argumentative, narrative or informational text appears within social studies, science, media-driven, and literary contexts will help students better understand assignments’ designs and therefore meet higher standards than if each teacher had his/her own requirements.

Courses with low expectations have students do work that they can already accomplish. Educators who want to push their students, though, need to create the means to help all students achieve these high standards. When teachers and administrators begin by learning who students are and what strengths and struggles they have, appropriate pedagogical tactics can be designed and clearly communicated to students and families. Simply said, people won’t hit a target they don’t know is there. In a standards-based learning world, students ought to be fully aware what’s being asked of them. Educators have to help students understand why they’re learning particular content and skills and what each looks like when completed. For example, if the goal is to write an editorial piece that’s to be submitted to a professional news outlet, educators must help students find a variety of such articles to read and an interesting topic on which to write their own.

Finally, teachers with high expectations will design units around open-ended essential questions with embedded formative benchmarks. Students should be allowed to explore, create, synthesize, and apply the skills and knowledge they’re acquiring instead of stopping at being able to identify, label and define information. With multiple means and points of ongoing assessment in place, educators will be able to individually support students as needed, keeping the next stage of their work towards high expectations always at Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development.

Sunday, September 29, 2013

Teachers' Stress: Reasons for it and Ways to Help

I’ve just come across this understated but extremely timely and important post on the LinkedIn group for the National Association of Secondary School Principals by Dr. Marc Tinsley (@DrTinz) http://linkd.in/1bQfhLy . It’s a limited survey from one inservice day at a high school, but with a few brief statistics, he’s got me thinking about the connection between teaching and stress level. As is all too noticeable, issues of teacher burnout, the amount of stress involved in educators’ work and how stress affects people’s general health and outlook are deeply relevant in today’s schools. It’s timely because the school year’s just starting out - so there’s a chance to help - and important because teacher burnout is unnecessary and a true threat to the quality of teaching in our future.

For starters, please know that I haven’t been a full-time teacher in 4 years, but being a full-time high-school English teacher for 10 years and then an ELA department coordinator and assistant principal lends me a global perspective that I do like to have on issues like this. Secondly, I know that other professionals within schools and school systems are stressed, but I’m not going to write about them here. If you want, for example, to read about the clearly overwhelming world of school principals, you ought to read and follow a Blog by John Falino (@johnfalino1), Prinicipal at Dobbs Ferry High School in Westchester, NY, who in this post http://bit.ly/1bQguCE writes about trying to prioritze his work and links to other people who have attempted to list all that principals do. It’s a mind-bending task list, but I’m going to focus on teachers.

If you’ve read Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle, you’ll best understand my introduction’s final point. In it, he creates a number of words that help to define a life-outlook / religion known as Bokononism. In this case, we’re talking about “teachers” as what Vonnegut would call a “granfalloon,” a group of people who are referenced together and have some similarities, but aren’t actually similar enough to be measured as a group. (Think: teenagers, Southerners, Musicians, etc) Of course, we can stereotype and generalize, but I won’t. For now, I want to only consider those at the top of our profession, those teachers who are fully actualizing their job description and then some. It’s those who fulfill all philosophical and tactical expectations for the work. Think of the Hollywood movie teacher of yesteryear - before the profession became vilified - and see the stress that led up to divorce, heart failure, jail time, bankruptcy, etc in films like Stand and Deliver, Lean on Me, Dead Poets’ Society, and Freedom Writers. Some of these are fictional or fictionalized, but there are legions of teachers - some of whom I’ve had the privilege of knowing and working closely with - that are very real and equally in danger of stress, poor health and burnout. Am I saying that there are teachers who don’t fit these qualifiers? Yes, I’ve seen them, and I’ve worked with them too. Some from this group have stepped up and improved their attitude and work while the others...well...not so much, but this is an issue for other times. I’m going to explore a bit about the people who strive to do it all.

I want to open the dialogue because, as an administrator, I think that we have to work to help alleviate as many pressures as possible. We must be reflective enough to understand the few tweaks we can do to our outlook, attitude, and systems that’ll help teachers lower their stress levels, which is better for them, their students and the overall school culture in both the short and long terms.

Sources of teachers’ stress, as I see it:

1) The length of the “work day.” While it’s true that school hours aren’t very long, the teachers I know put in almost as many hours outside of scheduled hours as during the day with students. When we consider paper grading, lesson planning, meetings, communication with parents and room set up, we start to get the picture.

2) Let’s add to the time factor by saying that education - as a profession - is changing at a blistering speed. In order to keep up with the students’ changing needs, the absolute expectation of hitting the needs of all students and the omnipresent expectations of the political and economic machines that now more than ever write our rule book, teachers need to be constantly learning. What we are doing about that is increasing our connectedness and research. We’re reading, discussing, trying, and learning about everything from international literary titles to brain research and iPad apps.

None of this is helping teachers relax and get needed sleep.

3) The moral and social justice aspects of the job mean that every moment holds a tremendous amount of emotional weight. We know what happens to our students if we don’t bring our A game. Since most excellent teachers are either type-A people who succeeded in school because of their passions, tenacity and refusal to fail and want the same for their students or they are type-A people who struggled in schools and are going to work themselves to the bone in order to help their students avoid the same experience(s).

4) Weltschmerz is the depression experienced when people’s expectations are crushed by the physical reality of a situation. There is an alarming rate of new teachers who are leaving the profession within the first five years. Is it student apathy, deep literacy issues, big testing, unsupportive administration, a lack of strong technology or something else altogether? Probably some of all of the above. What I know is that the classrooms, schools and profession they dreamed of is full of things they neither expected nor are prepared for/interested in working on.

5) The most distressing source of stress listed in the survey was student behavior. I’ve worked in a few relatively calm schools and a few schools with what I call “a lot of personality.” Our truth, which I guess educators can whine and moan over if they’d like, is that there are a lot of students who need help understanding what affective standards look like in a variety of situations. They need to practice how they carry themselves in classrooms, hallways, sporting events, restaurants, job interviews, live theaters and a host of other scenarios in the same way that we teach them how to hold debates, clean up art supplies or participate in socratic seminars. This is such a stressor because 1) Many educators don’t feel as if it’s their job to teach these things, and a lot of students and families would agree. 2) Affective lessons take a long time and a lot of patience before they’re internalized, usually meaning that some students may not “get better” at some things by the end of one year. 3) the tough one is that those of us who accept this as a vital part of what we do, know that the first step in fixing it is to reflect on our own expectations and look at our students with empathy / understanding instead of pity and frustration.

This may sound troubling, but as a solutions-based administrator, I want us to remember that a lot of these issues can be averted or solved through some top practices around systems:

1) Create supporting systems for all teachers, but especially new hires. Teachers’ success is important to them, their students and you, so be there for them. Even if you don’t see evidence of things going well in their classes, give constructive and specific feedback and examples so that the teacher(s) can grow. On top of your administration team’s 1:1 time with them, find a way to set up a new hires’ committee, horizontal grade-level teams, vertical content-area teams and time for teachers to see other’s best practices in action. Don’t forget that you’re a manager in the building. In my opinion, having employees means that you’re willing to give timely, proactive, sincere and professional feedback, especially if something is going well. Give them the knowledge and the chance to improve.

2) Ditch any unproductive and unnecessary asks. There is so much on teachers’ plate right now with technologies to learn, the Common Core to adapt to, new testing structures to become familiar with and, of course, their students to understand. If you are asking anything of them that’s not vital and directly attached to student needs, it just needs to go. Don’t change things for the sake of changing things. Focusing on whatever is truly needed by students can help you rally the whole school around an effort.

3) Help teachers recognize wins. Most master teachers I know are hyper-critical of themselves, only seeing what else they could have done and what didn’t go perfectly. Their students get all the credit for great learning moments, and they give themselves all of the blame for struggles of any sort. Send notes, send emails, find them to point things out in person and share their wins publically if they’ll let you. Try to set up faculty-run pd workshop days where those who do things well share with the faculty as a means of recognizing their excellence.

4) Make sure that everyone knows that school is a place where people learn. Nobody is a permanent expert. We have to allow ourselves, students and teachers to make mistakes and be imperfect. Do away with any vestige of “gotcha politics” and turn your observation and evaluation system into a chance to dialogue with teachers about how their lessons are or are not helping students meet standards that are set by content masters and grade-level teams. Especially now that most states have new teacher evaluation rubrics coming on board, we need to ensure that teachers have a chance to understand it and practice adhering to its rubrics.

5) Get your teachers connected. This one may be a tough sell in some cases because you’ll essentially be talking with teachers who may already feel themselves stressed, overworked, tired, and annoyed with technology, and you’re going to suggest that they spend chunks of their precious “down time” online connecting with other educators, reading blogs and coming to understand new resources and methodologies. It may sound counterintuitive, but as Todd Nesloney (@TechNinjaTodd) tells us in a recent post http://t.co/540AVsFydR , “How my PLN (Professional Learning Network) Saved My Career,” connecting with educator from across the country and even the world can be refreshing and revitalizing. In the same sense as the adage that tells us we have to spend money to make money, it is true for many, myself included, that we’ve had to invest a decent amount of time in order to lend a renewed sense of potential and purpose to our professional work. The group with whom I’m connected - thanks to John Falino’s influence (see above reference) - is unshakably positive, hopeful, supportive, creative, innovative and insistent that the work we discuss is always done for the benefit of student’s learning. There are a lot of places for them to go to connect, but I’d have to recommend using Twitter. I’m going to suggest that administration signs up first as a “walk the walk” gesture.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)