“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.”

- Margaret Mead

I just finished listening to Mona Hanna-Attisha read her first-person account (via Audible) of the political and humanitarian crisis surrounding lead-tainted water in Flint, Michigan. I can’t say that it’s changed me because it’s one of those books that sadly reinforces my cynicism. Her story stands as a giant reminder to me that people can be awful, especially when they are left unchecked and driven by power, ego, money, and professional status. Even when I was a high-school English teacher, I was always careful to talk about books as being “important,” teaching things because they were in the canon, or really calling anything a must read. Regardless of how much I love a book, how successful it’s been with some classes, how much I think students can learn from a book, or how relevant I think a book is, I also know that there are dozens (if not more) books that cover the same or similar themes and connect with people in a similar way. I don’t like to pit authors, stories, or any content against each other. I just don’t see the need.

That being said, I absolutely believe that schools need to play a huge role in children’s civic education (MA has actually just passed legislation mandating this as part of the Dept of Elementary and Secondary Education’s update to the state’s history and social studies standards.), and I believe that this book could serve as a tremendous foundation for this work.

My case:

The Title

On a literal level, the title is about lead in Flint’s water, which although it was found in amounts far surpassing legal “action levels,” remained unseen and came from pipes underground, which again can’t be seen. While there were many moments when the water coming from Flint taps was dirty and brown, it was more often the case that people weren’t able to tell. Anyhow, dirt in the water is gross; lead in the water is invisible, corrosive and developmentally debilitating with irreversible effects.

There’s another aspect here that follows the adage about people seeing what they choose to see and ignoring what they choose to ignore. This isn’t perspective, which I believe is the way we think about something we see; this is about people willfully “not seeing” something - and some people - until they got caught. Lead in people’s water can be ignored because it can’t be seen. It can be ignored because the historical fuss about lead is with lead paint (We can all see chipping window paint.), so lead in water hasn’t been explored enough to instantly raise concerns. Flint’s water being tainted could be ignored because their political voice was taken from them, and it isn’t a city populated with economic and political clout or connections.

Finally, what people’s eyes don’t see is their government’s leaders being willing to purposefully lie, deceive, and put their constituents directly in harm’s way. We understand the idea of checks and balances but believe it’s for times of clarity or to stop a branch from overreaching. We also understand the need for advocacy, but it’s preferably to sway someone’s opinion towards a particular cause. What we most often allow ourselves to ignore, though, is the idea of leaders acting in ways that counter the public good, doing things that don’t at all service a humanistic agenda. While I’ll never try to raise a generation of cynics, it’s important that students become skeptical of anyone who answers their concerns with “Don’t worry. Everything’s fine. I’ve checked.”

Professional Purpose:

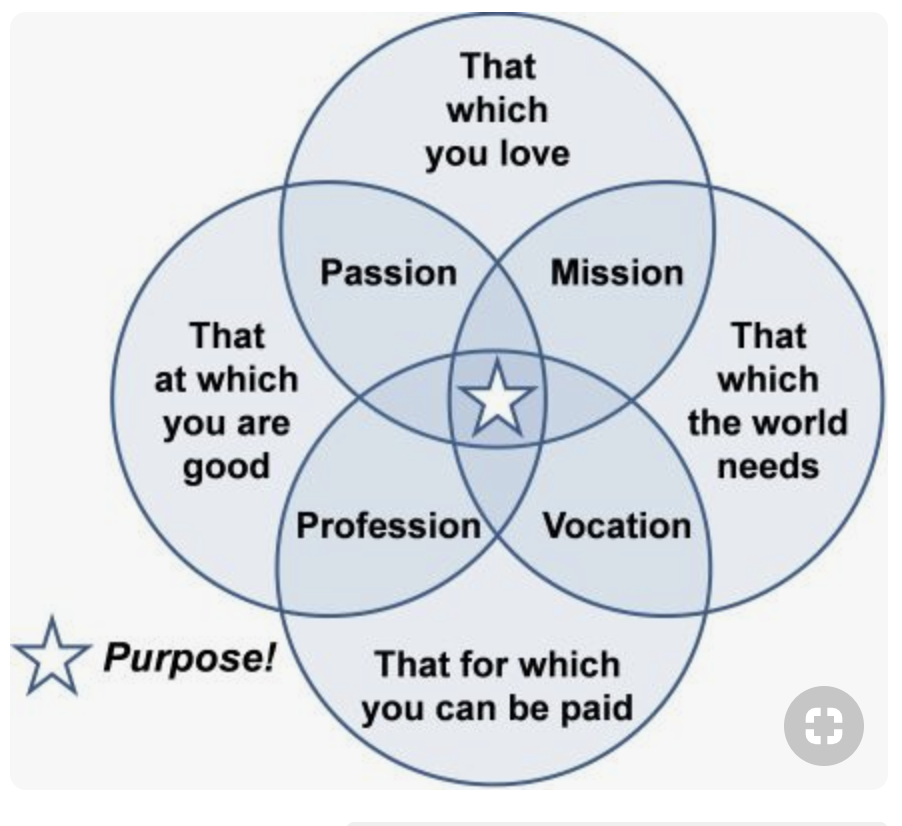

Dr. Hannah-Attisha would love this graphic about finding a sense of purpose. She is already a pediatrician, so anything she does professionally has her caring for kids and families. On top of that, though, she works at an urban public hospital as a means of supporting a community that truly needed support, and then became in charge of the residency program as a means of extending her influence across many doctors instead of just supporting the patients she personally saw.

This wasn’t enough for her, though. Because she see the bigger picture of her career, the context in which pediatricians fit into their patients and patients’ families’ and communities’ lives, she understands that caring for them means advocating for their needs, whether that happens as a result of peers’ decisions, hospital policies, or, as in this case, the power structure that’s established in favor of politicians, business, and non-marginalized racial/ethnic groups. She doesn’t question taking this fight on because she knows that Flint’s children need her and that she therefore doesn’t have choice whether or not to get involved. As educators, I hope we feel this way as well. This book, to me, felt a lot like Jonathan Kozol’s Amazing Grace about the education and living conditions in Mott Haven, NY, a once-forgotten neighborhood in the Bronx, where I had the sincere pleasure of working with a tireless and fully student-centered principal.

Personal and Societal Connections:

All powerful stories will be full of connections and context, meaning that what “Dr. Mona’s” eyes do see is the way the story of Flint connects with both her own family’s stories and the bigger picture behind this particular tragedy. She does a beautiful job of weaving in both the stories of her family’s support, frustrations, and struggles throughout the busiest times of this conflict and her extended families stories of their heritage and international emigration. She also knows that Flint’s water tragedy is a story of institutional racism and bullying as powerful, well-connected groups conspire to ignore and disregard the voices of those without social and political clout and calls out these people in her work and throughout this book.

The Good Fight:

This is known as a “fight” instead of just an “awkward text” or “tough phone call” because things don’t change overnight. She had to work tirelessly to even accomplish her piece of the victory in Flint. She has been criticized, actually, for this book making it seem like she was a bigger player in the overall win than she was, but I think she had to keep the book focused and wanted to ensure that her readers understand how much effort it takes to accomplish a policy overhaul at that scale. The book chronicles her impressive and creative data collection, team building, and public relations campaign. This was, of course, on top of doing her job and being a mom. I actually wish there would’ve been an example of her daily agenda book published as part of the story. I can’t even imagine all that she repeatedly accomplished every day and the emotional toll that being so tired, mocked and belittled by the government must have taken on her.

The Writing:

This book is absolutely accessible to all students and - other than swearing a few times - it’s PG. It’s one of those great opportunities to have students of all literacy abilities come together for amazing discussions and extension work. Using this book in a class could be a perfect way to support literacy while discussing huge ideas. It’s got plenty of science, sociology, and politics, so it’s clearly not fluff, but it’s not overdone to the point of inaccessibility.

The Classroom Curriculum:

If I ever get the opportunity to teach a class with this book, I could think of so many ways to make fully engaging and important to kids.

- Researching other moments of people whistleblowing and/or fighting against hugely powerful people and forces. Compare the efforts and create a winning play list of sorts. I’m thinking about tobacco, #metoo, gun control, opioids, deepwater horizon / Exxon-Valdez, #occupywallstreet, #blacklivesmatter, etc.

- Show popular films of this sort: The Insider, Erin Brokovitch, The Post, Bully, Roger and Me.

- Research (genius-hour style) any of the related topics such as urban infrastructure, racial segregation (think: schools, politics, public transportation, etc), role of state v local government on local issues.

- Read any fiction related to “otherness.” I especially like Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s story “The Yellow Wallpaper” since Hanna-Attisha is regularly dismissed by male politicians and scientists as being “hysterical.”

- Have students choose topics for which to advocate. They can be at the classroom, school, community or larger level(s). Put together a plan. Do some research. Distribute a survey. Create a petition. Walk with picket signs. Write letters. Get a feel for what happens. I’ve seen this done individually or as class-by-class projects.